Les tableaux (vecteur, matrice)

Contenu

7. Les tableaux (vecteur, matrice)¶

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

from IPython.display import HTML,display,IFrame,Video

from IPython.display import YouTubeVideo,Markdown

display(Markdown("**Video du cours: Introduction**"))

YouTubeVideo('1Hq4vJBIGhg')

Video du cours: Introduction

Astuce

pour tester les programmes Python, vous pouvez vous connectez sur un serveur Jupyter, par exemple, pour les étudiants Lyon1 https://jupyter.mecanique.univ-lyon1.fr

7.1. Tableau 1D¶

structure de données pour représenter un vecteur

tableau 1D : liste de n éléments du même type (entier ou réel) (n = dimension du tableau)

en mathématique: \(\mathbf{X} \in \mathcal{R}^n \)

en algorithmique: X tableau de n réels (contenant les composantes de X)

élément d’un tableau : X[i] \(\equiv\mathbf{X}_{i+1}\)

attention on compte à partir de 0, donc i varie de 0 à n-1

7.1.1. Exemple: point dans l’espace¶

le point P dans l’espace \(\mathcal{R}^3\) de coordonnées cartesiennes: $\( \mathbf{OP}=\left[\begin{array}{c} 1.\\ 3.\\ -0.5 \end{array}\right] \)$ est représenté par un tableau de réels de dimension 3, tel que:

P=[1.,3.,5.] (i.e. P[0]=1., P[1]=3.0, P[2]=5.0)

display(Markdown("**Video du cours: Tableaux 1D**"))

YouTubeVideo('RMB83wVk8Wc')

Video du cours: Tableaux 1D

Attention

Les vidéos utilisent un ancien interpréteur python 2.7, pour lequel print est un mot clé,

soit print 'bonjour'.

Avec Python 3, print est une fonction et il faut donc utiliser des parenthèses,

soit print('bonjour')

7.1.2. Tableau numérique sous Python¶

plusieurs structures de données possible (list, array, ..)

mais on utilisera essentiellement la structure array de la bibliothéque numpy

import numpy as np

P = np.array([1., 3., 5.])

print(P)

print(type(P))

print(P.size)

print(P[1])

print(type(P[1]))

[1. 3. 5.]

<class 'numpy.ndarray'>

3

3.0

<class 'numpy.float64'>

7.1.3. visualisation de l’exécution¶

utilisation du site : http://pythontutor.com

vous pouvez copier l’exemple de code python sur le site pour l’exécuter

P = [1.,3.,5.]

x = P[2]

y = (P[0]+P[1]+P[2])/3

z = P[3]

display(Markdown("**Visualisation de l'execution sur le site pythontutor**"))

Video("VIDEO_COURS/pythonlive_tab1.mp4", embed=True,width=700, height=300)

Visualisation de l'execution sur le site pythontutor

7.1.4. Indice d’un tableau¶

attention pour un tableau de dimension n : indice \(0 \le i \lt n\)

print(P[2])

print(P[3])

5.0

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

IndexError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-6-53bfb96ce013> in <module>

1 print(P[2])

----> 2 print(P[3])

IndexError: index 3 is out of bounds for axis 0 with size 3

7.1.5. Manipulation de tableaux 1D en Python¶

7.1.5.1. création d’un tableau¶

à partir d’une liste (entre [ ]): ** array(liste) **

dimension = nbre d’éléments de la liste

type = type des éléments de la liste

display(Markdown("**Video du cours: Manipulation des tableaux 1D**"))

YouTubeVideo('SsFtJ0uXTTM')

Video du cours: Manipulation des tableaux 1D

Attention

Les vidéos utilisent un ancien interpréteur python 2.7, pour lequel print est un mot clé,

soit print 'bonjour'.

Avec Python 3, print est une fonction et il faut donc utiliser des parenthèses,

soit print('bonjour')

Q = np.array([1., 2.])

print(Q[0], type(Q[0]))

I = np.array([1, 2])

print(I[0], type(I[0]))

1.0 <class 'numpy.float64'>

1 <class 'numpy.int64'>

7.1.5.2. tableaux particuliers¶

tableau de 0.0 ou de 1.0 : zeros(n) ou ones(n) ( n dimension)

tableau de n valeurs non initialisées (attention !!!): empty(n)

X = np.zeros(5)

print(X)

Y = np.ones(3)

print(Y)

Z = np.empty(3)

print(Z)

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[1. 1. 1.]

[1. 1. 1.]

tableau de liste de valeurs: arange(debut, fin, pas)

print(np.arange(0, 10, 1))

print(np.array(range(10)))

print(np.arange(0., 10., 1.5))

[0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9]

[0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9]

[0. 1.5 3. 4.5 6. 7.5 9. ]

intervalle: linspace(debut, fin, nbre d’éléments)

print(np.linspace(0, 10, 11))

print(np.linspace(0, 10, 3))

[ 0. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10.]

[ 0. 5. 10.]

valeurs aléatoires: random.rand(nbre)

print(np.random.rand(5))

[0.44394066 0.7345521 0.69825174 0.47305282 0.38657288]

liste de compréhension [ exp for i in range(n) ]

X = np.array([i*i for i in range(5)])

print(X)

[ 0 1 4 9 16]

spécification du type des éléments du tableau: argument dtype (int,float,..)

I = np.zeros(3, dtype=int)

print(I)

print(type(I), type(I[0]))

[0 0 0]

<class 'numpy.ndarray'> <class 'numpy.int64'>

7.1.5.3. taille et élément d’un tableau¶

nbre d’éléments du tableau X: X.size ou len(X)

taille du tableau X: X.shape

n = 5

X = np.zeros(n)

print(X.size, len(X), X.shape)

5 5 (5,)

accès aux éléments: premier X[0] et dernier X[-1]

X = np.arange(1., 2., 0.2)

print(X)

print(X[0], X[-1])

[1. 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8]

1.0 1.7999999999999998

sous-tableau: X[deb:fin:pas]

X = np.arange(0, 10, 1)

print(X[:])

print(X[1:3])

print(X[::2])

print(X[1:-1])

[0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9]

[1 2]

[0 2 4 6 8]

[1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8]

7.1.5.4. aliasing et copie de tableau¶

aliasing par défaut: Y=X ne crée pas un nouveau tableau mais un alias

de même Y=X[:] (contrairement aux listes)

copie explicite: Y[:]=X[:]

ou ** Y = X.copy() **

X=np.zeros(2)

Y=X

Z=np.zeros(2)

Z[:]=X[:]

Y[0]=1

Z[0]=2

print("X=",X,"Y=",Y,"Z=",Z)

X= [1. 0.] Y= [1. 0.] Z= [2. 0.]

7.1.5.5. boucle sur les éléments d’un tableau¶

boucle for : for i in range(n):

n = 5

X = np.zeros(n)

for i in range(n):

X[i] = i*i

print(X)

[ 0. 1. 4. 9. 16.]

7.2. Exemples et exercises d’utilisation de tableaux 1D¶

display(Markdown("**Video du cours: Exemple d'utilisation de tableaux**"))

YouTubeVideo('_tm7hOIVh2c')

Video du cours: Exemple d'utilisation de tableaux

Attention

Les vidéos utilisent un ancien interpréteur python 2.7, pour lequel print est un mot clé,

soit print 'bonjour'.

Avec Python 3, print est une fonction et il faut donc utiliser des parenthèses,

soit print('bonjour')

7.2.1. Exemple: produit scalaire¶

Calcul du produit scalaire scal de 2 vecteurs X,Y:

Remarque si X=Y \(\rightarrow\) norme

Algorithme produit scalaire

Algorithme ProdScal(X,Y)

n = dimension(X) (et Y)

scal=0

pour i de 0 a n-1

scal = scal + X[i]*Y[i]

fin pour

retour scal

Programme Python produit scalaire

def ProdScal(X,Y):

""" calcul le produit scalaire de 2 vecteurs """

n=X.size

scal = 0

for i in range(n):

scal = scal + X[i]*Y[i]

return scal

#

X = np.random.rand(2)

Y = np.random.rand(2)

print("X =", X)

print("Y =", Y)

print("X.Y =", ProdScal(X,Y), ' ou', np.dot(X, Y))

X =

[0.85130975 0.38405958]

Y = [0.75229749 0.28422782]

X.Y = 0.7495986105890232 ou 0.7495986105890232

7.2.2. Exercices¶

Test de colinéarité de 2 vecteurs

Normalisation d’un vecteur

7.2.2.1. Test de colinéarité de 2 vecteurs¶

Ecrire une fonction qui teste la colinéarité

colineaire(U,V)

Attention à la précision

7.2.2.2. Normalisation d’un vecteur X¶

Ecrire une fonction python qui normalise un vecteur X

Xn = normalisation(X)

attention au cas X=0

7.3. Tableau 2D¶

structure de données pour représenter une matrice

tableau 2D : liste de \(n*p\) éléments du même type (entier ou réel) (n,p = dimensions de la matrice)

en mathématique: \(\mathbf{A} \in \mathcal{R}^{n,p} \)

en algorithmique: A tableau de \(n*p\) réels (contenant les composantes de A)

élément i,i du tableau : A[i,j] \(\equiv\mathbf{A}_{i+1,j+1}\)

Attention on compte à partir de 0, donc i varie de 0 à n-1 et j de 0 à p-1

7.3.1. Exemple: matrice de rotation dans \(\mathcal{R}^2\)¶

Rotation \(\theta\) d’un repère :

représenté par un tableau de réels de dimension \(2*2\), tel que:

R=[[cos(theta),-sin(theta)],[sin(theta),cos(theta)]]

(i.e. R[0,0]=cos(theta), R[0,1]=-sin(theta), R[1,0]=sin(theta), R[1,1]=cos(theta))

remarque theta est une variable contenant la valeur de l’angle

display(Markdown("**Video du cours: tableaux en 2D**"))

YouTubeVideo('5Tl6KDelqKI')

Video du cours: tableaux en 2D

Attention

Les vidéos utilisent un ancien interpréteur python 2.7, pour lequel print est un mot clé,

soit print 'bonjour'.

Avec Python 3, print est une fonction et il faut donc utiliser des parenthèses,

soit print('bonjour')

7.3.2. Matrices en Python¶

bibliothèque numpy: array, dimension couple (tuple) (n,p)

7.3.2.1. création de tableaux 2D¶

explicite

A = array([[1.,2.],[3.,4.]])

fonctions: zeros, ones,.. : identiques en 1D en remplaçant n par (n,p) (voir doc numpy)

import numpy as np

theta = np.pi / 3

R = np.array([[np.cos(theta), -np.sin(theta)],

[np.sin(theta), np.cos(theta)]])

print(R)

print(type(R))

print(R.size, R.shape)

[[ 0.5 -0.8660254]

[ 0.8660254 0.5 ]]

<class 'numpy.ndarray'>

4 (2, 2)

A = np.array([[1.,2.],[3.,4.]])

Z = np.zeros((3, 2))

X = np.reshape(np.arange(6),(2,3))

print(A.shape,Z.shape,X.shape)

(2, 2) (3, 2) (2, 3)

7.3.2.2. taille et éléments d’un tableau 2D¶

nbre total d’éléments du tableau A: A.size ou len(A)

par dimension A.shape

élément: ** [i, j]** (à partir de 0)

sous-matrices (convention identique en 1D)

ligne i : A[i, :]

colonne j : A[:, j]

A = np.array([[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]])

print("A=\n",A, "\nA11 =",A[1,1] ,"dim A=", A.shape)

B = A[:, 0:2]

print("B=\n",B, "\nB11 =",B[1,1] ,"dim B=", B.shape)

C = A[1, :]

print("C=\n",C, "\nC1 =",C[1], "dim C=",C.shape)

A[1,1]=0

print("B=\n",B)

print("C=\n",C)

A=

[[1 2 3]

[4 5 6]]

A11 = 5 dim A= (2, 3)

B=

[[1 2]

[4 5]]

B11 = 5 dim B= (2, 2)

C=

[4 5 6]

C1 = 5 dim C= (3,)

B=

[[1 2]

[4 0]]

C=

[4 0 6]

7.3.2.3. équivalence avec les tableaux 1D¶

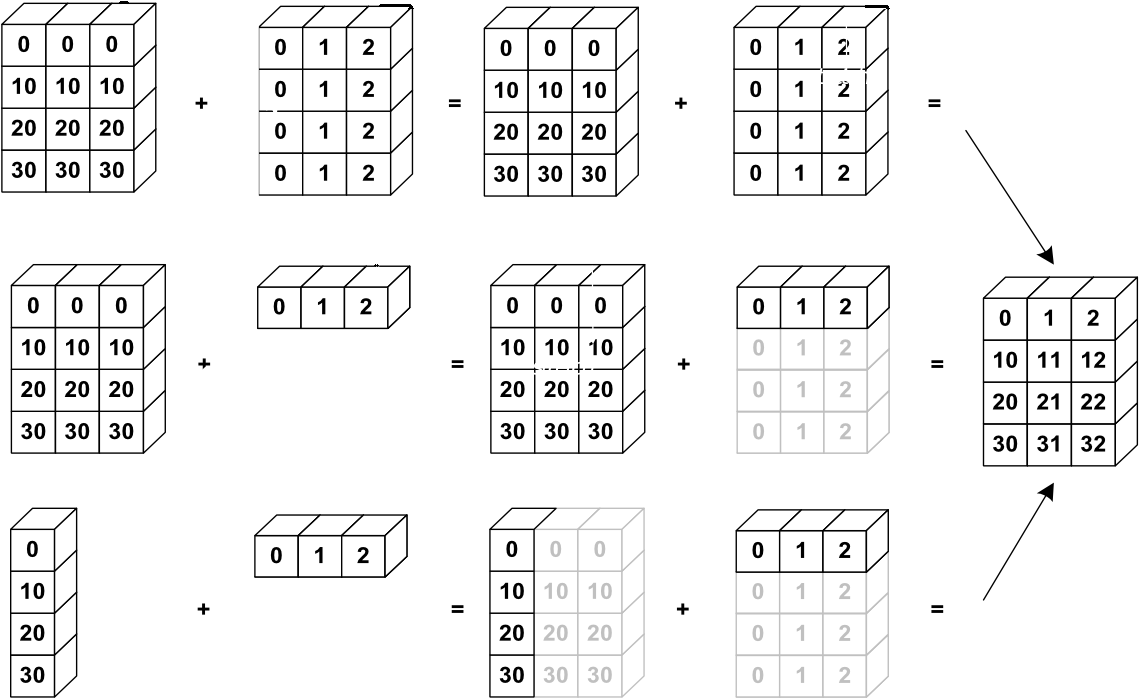

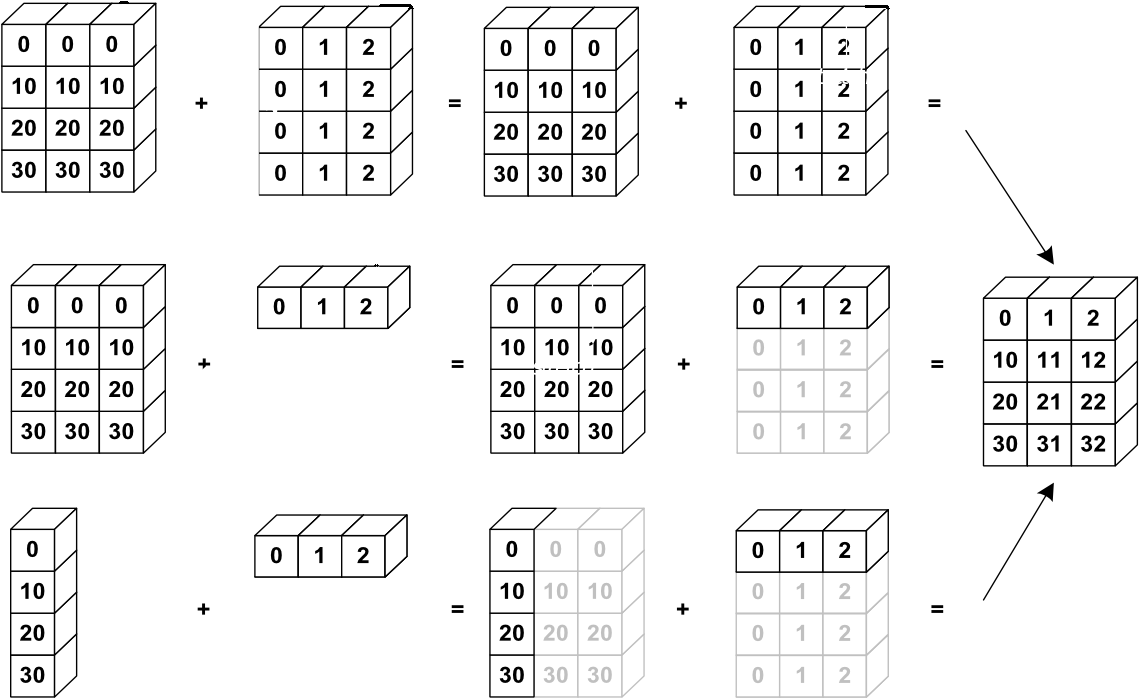

\(A\) tableau 2D (array 2D) \(n*p\) réels \(\equiv\) \(B\) tableau 1D de même dimension globale \(np\)

les données sont identiques, seul l’accès est différent:

reshape(tableau,dimension) (attention aliasing !!)

\(B = A\)

\(A_{i,j}\) pour \(i=0,n-1\) et \(j=0,p-1\)

\(B_k\) pour \(k=0..np-1\)

\(A_{i,j}\equiv B_k\) avec \(k=i*p+j\) (stockage par ligne C/C++)

display(Markdown("**Video du cours: manipulation des tableaux 2D**"))

YouTubeVideo('I-JAdP7PzIs')

Video du cours: manipulation des tableaux 2D

Attention

Les vidéos utilisent un ancien interpréteur python 2.7, pour lequel print est un mot clé,

soit print 'bonjour'.

Avec Python 3, print est une fonction et il faut donc utiliser des parenthèses,

soit print('bonjour')

A = np.array([[1., 2., 3.], [4., 5., 6.]])

B = np.reshape(A ,6)

C = np.reshape(A, (3, 2))

print("dim A =", A.shape," A=\n",A)

print("dim B =", B.shape," B=\n",B)

B[2] = 0

print("B=\n",B)

print("A=\n",A)

print("C=\n",C)

dim A = (2, 3) A=

[[1. 2. 3.]

[4. 5. 6.]]

dim B = (6,) B=

[1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6.]

B=

[1. 2. 0. 4. 5. 6.]

A=

[[1. 2. 0.]

[4. 5. 6.]]

C=

[[1. 2.]

[0. 4.]

[5. 6.]]

7.3.2.4. Copie et aliasing¶

aliasing = noms de variable différents, mais données partagées

aliasing par défaut sous python: ** B=A **

sinon copie explicite: C[:,:]=A[:,:]

A=np.zeros((2,2))

B=A

B[0,0]=2

C=A.copy()

C[0,:]=[3,4]

print("A=",A,"\nB=",B,"\nC=",C)

A= [[2. 0.]

[0. 0.]]

B= [[2. 0.]

[0. 0.]]

C= [[3. 4.]

[0. 0.]]

7.3.3. Exemple: produit matrice-vecteur¶

Calcul du produit matriciel Y=A X:

Algorithme produit matrice-vecteur Y = A X

Algorithme MatVec(A,X)

n,p = dimension de A

Y = tableau(n)

pour i de 0 a n-1

Y[i]=0.

pour j de 0 a p-1

Y[i]=Y[i]+A[i,j]*X[j]

fin pour j

fin pour i

retour Y

Programme Python produit scalaire

def MatVec(A,X):

""" calcul le produit Y=A.X de A par X """

n,p = A.shape

Y = np.zeros(n)

for i in range(n):

S = 0.

for j in range(p):

S += A[i, j] * X[j]

Y[i] = S

return Y

#

n, p = 3, 2

A = np.reshape(np.arange(n*p), (n, p))

X = np.array(np.arange(p))

print("A =\n",A)

print("X =",X)

print("Y =",MatVec(A,X))

A =

[[0 1]

[2 3]

[4 5]]

X = [0 1]

Y = [1. 3. 5.]

7.3.4. Exercices¶

Calcul du produit de 2 matrices

Calcul de la matrice de Vandermonde d’ordre n

7.3.4.1. Produit matrice-matrice¶

\(\mathbf{C} = \mathbf{A}\ \mathbf{B} \) pour \(\mathbf{A} \in \mathcal{R}^n\times\mathcal{R}^p\) , \(\mathbf{B} \in \mathcal{R}^p\times\mathcal{R}^q\) et \(\mathbf{C} \in \mathcal{R}^n\times\mathcal{R}^q\)

7.3.4.2. Matrice de Vandermonde¶

Intervient dans le problème de la détermination du polynôme d’interpolation de degré \(n\) passant par \(n+1\) points \(\{x_i,y_i\}_{i=0,n}\)

7.4. Boucle en Python sur les tableaux¶

7.4.1. itérations avec un indice¶

for i in range(len(Tab)):

7.4.2. itérations sur les éléments val d’un tableau Tab (ou d’une liste)¶

for val in Tab:

# calcul du carré de la norme d'un vecteur

X = np.random.rand(100)

norm2 = 0.0

for x in X:

norm2 = norm2 + x * x

print(norm2)

32.19621271587842

7.4.3. itérations avec indice et valeur (enumerate)¶

for i,val in enumerate(Tab):

# determination du max d'un tableau

X = np.random.rand(10)

print(X)

xmax = X[0]

imax = 0.

for i, x in enumerate(X):

if x > xmax:

xmax = x

imax = i

print("xmax =", xmax, " pour i =", imax)

[0.49482849 0.10495686 0.33167636 0.78296994 0.32300653 0.38819826

0.22437685 0.73524524 0.96842014 0.8125108 ]

xmax = 0.9684201356000487 pour i = 8

7.4.4. boucle avec un indice décroissant (reversed)¶

for i in reversed(range(n)):

7.4.4.1. exemple : permutation circulaire vers la droite¶

# permutation des valeurs d'un tableau vers la droite: X[i+1]=X[i]

X = np.random.rand(4)

print(X)

last = X[-1]

for i in reversed(range(1, X.size)):

X[i] = X[i-1]

X[0] = last

print(X)

[0.51917772 0.42967876 0.6077558 0.50939431]

[0.50939431 0.51917772 0.42967876 0.6077558 ]

7.4.5. boucles de très grande taille: xrange¶

pour des boucles de très grandes tailles (n > 100 000) on peut utiliser

for i in xrange(n)

au lieu de

for i in range(n)

Exercice: modifier l’algorithme pour effectuer une permutation circulaire vers la gauche

7.5. Notation matricielle (à la Matlab)¶

display(Markdown("**Video du cours: Notation matricielle avec Numpy**"))

YouTubeVideo('Zsd326timCw')

Video du cours: Notation matricielle avec Numpy

Attention

Les vidéos utilisent un ancien interpréteur python 2.7, pour lequel print est un mot clé,

soit print 'bonjour'.

Avec Python 3, print est une fonction et il faut donc utiliser des parenthèses,

soit print('bonjour')

7.5.1. Efficacité -> boucles dans la bibliothéque numpy¶

opérations (terme à terme) sur les vecteurs +,-,*,/

X = np.random.rand(3)

Y = np.random.rand(3)

print("X=",X, "\nY=",Y, "\nXY=",X*Y)

X= [0.85522068 0.94264644 0.46860517]

Y= [0.77628044 0.42333267 0.28003526]

XY= [0.66389109 0.39905304 0.13122597]

fonctions mathématiques (terme à terme)

print(np.cos(X))

[0.65605197 0.58764881 0.89219912]

7.5.2. Utilisez les fonctions de la bibliothéque numpy¶

opérations matricielle: fonction dot

produit scalaire, produit matrice-vecteur, produit matriciel $\( C= dot(A,B)\ \rightarrow\ C_{ij} = \sum_{k} A_{ik} B_{kj}\)$

print("X.Y=",np.dot(X,Y))

print("|X|=",np.sqrt(np.dot(X,X)))

A = np.random.rand(3,3)

print("A*X=",np.dot(A,X))

print("A*A=\n",np.dot(A,A))

X.Y= 1.194170092979542

|X|= 1.3563095243946734

A*X= [1.08627044 0.89119311 1.70088489]

A*A=

[[0.89934719 0.93943571 1.25764973]

[0.72761273 0.76873464 1.04065476]

[1.03639723 1.10354611 1.7707986 ]]

produit tensoriel interne (somme sur la dernière dimension): fonction inner $\( C= inner(A,B)\ \rightarrow\ C_{ij} = \sum_{k} A_{ik} B_{jk}\)$

print("inner(X,Y)=",np.inner(X,Y))

print("inner(A,X)=",np.inner(A,X))

print("inner(A,A)=\n",np.inner(A,A))

inner(X,Y)= 1.194170092979542

inner(A,X)= [1.08627044 0.89119311 1.70088489]

inner(A,A)=

[[1.08145037 0.86909567 1.22621867]

[0.86909567 0.70577447 1.00163501]

[1.22621867 1.00163501 1.68780818]]

produit tensoriel externe: fonction outer

print("outer(X,X)=\n",np.outer(X,X))

outer(X,X)=

[[0.73140242 0.80617073 0.40076083]

[0.80617073 0.88858231 0.44172899]

[0.40076083 0.44172899 0.2195908 ]]

somme et produit : fonction sum et prod

ainsi que de nombreuses autres fonctions (inverse, déterminant, ..)

voir la documentation numpy: http://docs.scipy.org/doc/numpy/reference

7.5.3. Aide sur les fonctions : help() ou TAB¶

help(fonction) ou fonction?

exemple

help(np.sum)

Help on function sum in module numpy:

sum(a, axis=None, dtype=None, out=None, keepdims=<no value>, initial=<no value>, where=<no value>)

Sum of array elements over a given axis.

Parameters

----------

a : array_like

Elements to sum.

axis : None or int or tuple of ints, optional

Axis or axes along which a sum is performed. The default,

axis=None, will sum all of the elements of the input array. If

axis is negative it counts from the last to the first axis.

.. versionadded:: 1.7.0

If axis is a tuple of ints, a sum is performed on all of the axes

specified in the tuple instead of a single axis or all the axes as

before.

dtype : dtype, optional

The type of the returned array and of the accumulator in which the

elements are summed. The dtype of `a` is used by default unless `a`

has an integer dtype of less precision than the default platform

integer. In that case, if `a` is signed then the platform integer

is used while if `a` is unsigned then an unsigned integer of the

same precision as the platform integer is used.

7.6. Bibliographie¶

transciption du célébre article de Edsger W. Dijkstra.

Numpy pour les utilisateurs de Matlab

ou comment traduire des programmes Matlab sous Python

7.7. Fin de la leçon¶